What does ext4 look like?

That is... if I start with a blank drive, a drive made completely of 0x00s, and then do mkfs.ext4, what does the drive, now embossed with ext4, look like?

I mean, what I wanted to see, is what it takes to transmogrify a bunch 0x00s, from "nothing" into the purposeful assemblage of bytes that is an ext4 filesystem.

At first I figured I’d try visualizing a live drive, like /dev/sda... but quickly figured 'dd' + 'live drive' could get me into trouble, so opted for adding a small secondary drive to my VM.

Then I thought, even with a virtual machine, working with 'dd' and /dev/sdX would be more trouble than it was worth. I then remembered I didn’t have to use drives at all, virtual or otherwise, I could just work with a regular file, configured as a loop device.

And it turns out mount/umount have evolved since I last experimented with loop devices... you don’t have to 'losetup' the loop device anymore just a simple:

# mount -o loop <foo_file> <bar_dir> # umount <bar_dir>

Is all that is required

Using a loop device simplified my efforts, and diminished the likelihood of a

dd accident.

So a little about what we’re looking at.

I always start with a blank file... that is a file created with 'dd' and a source of '/dev/zero'... the calculated size of the file correspond to a final image with eight blocks, each 64-pixels/bytes high, and 1024-pixels/bytes wide.

$ dd if=/dev/zero of=blockfile.ext4 bs=$((64 * 1024)) count=8

The output of this is predictable

$ od -x -A x blockfile.ext4 000000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 080000

But I wanted to see the difference between a zero file, and one with whatever structure mkfs.ext4 adds to the drive...

Of note: the size of drive I’m working with is too small for a journal... but thats okay... Doing a visualization which includes a journal I’m leaving for a future project.

So now the output of 'od' of the blockfile which mkfs.ext4 is run against, is a little more interesting... here we begin to see structure:

$ od -x -Ax blockfile.ext4 000000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 000400 0040 0000 0200 0000 0019 0000 01e2 0000 000410 0035 0000 0001 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 000420 2000 0000 2000 0000 0040 0000 0000 0000 000430 c737 5e10 0000 ffff ef53 0001 0001 0000 000440 c737 5e10 0000 0000 0000 0000 0001 0000 000450 0000 0000 000b 0000 0080 0000 0038 0000 000460 02c2 0000 046b 0000 927f 9037 d060 5e4c 000470 1b83 287a 7389 0001 0000 0000 0000 0000 000480 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 0004c0 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0003 0004d0 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0004e0 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 7da5 5d6c 0004f0 72c1 5b42 719d b2ee 63d5 d142 0001 0040 000500 000c 0000 0000 0000 c737 5e10 0000 0000 000510 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 000560 0001 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 000570 0000 0000 0104 0000 0015 0000 0000 0000 000580 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 0007f0 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 7d3f 9ace 000800 0006 0000 0016 0000 0026 0000 01e2 0035 000810 0002 0004 0000 0000 c571 4e0a 0035 4797 000820 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 000830 0000 0000 0000 0000 96a2 c509 0000 0000 000840 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 001800 ffff 002f 1fe0 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 001810 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 001830 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 8000 001840 ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff * 001c00 0002 0000 000c 0201 002e 0000 0002 0000 001c10 000c 0202 2e2e 0000 000b 0000 03dc 020a 001c20 6f6c 7473 662b 756f 646e 0000 0000 0000 001c30 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 001ff0 0000 0000 0000 0000 000c de00 e669 11f0 002000 000b 0000 000c 0201 002e 0000 0002 0000 002010 03e8 0202 2e2e 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 002020 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 0023f0 0000 0000 0000 0000 000c de00 0f7a 7b5d 002400 0000 0000 03f4 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 002410 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 0027f0 0000 0000 0000 0000 000c de00 3e04 8f88 002800 0000 0000 03f4 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 002810 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 002bf0 0000 0000 0000 0000 000c de00 3e04 8f88 002c00 0000 0000 03f4 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 002c10 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 002ff0 0000 0000 0000 0000 000c de00 3e04 8f88 003000 0000 0000 03f4 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 003010 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * 0033f0 0000 0000 0000 0000 000c de00 3e04 8f88 003400 0000 0000 03f4 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 003410 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 * [... snip ...]

But at the byte density provided by the output of 'od', trying to visualize the ext4 structure is like trying to visualize the structure of three deciduous forests by examining the leaves of a single tree... I wanted a picture which would let me "zoom out", giving me a better idea of what I was looking at...

So I came up with this... each blue block is 1024 pixels wide, and 64 pixels high... each pixel represents a single byte... Nothing much to see here, except a drive made entirely of 0x00s.

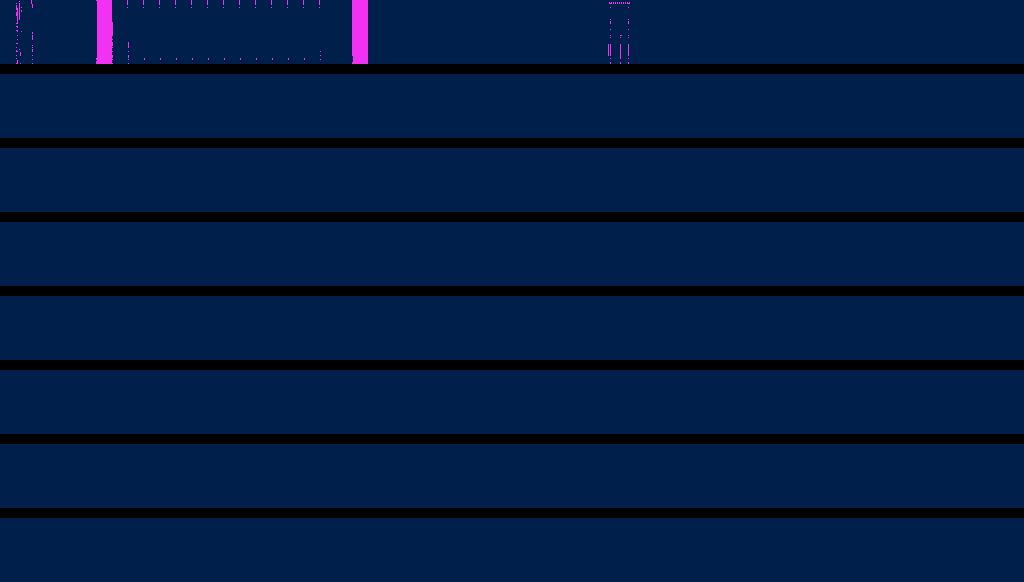

It starts to get interesting after creating the ext4 filesystem, and see this...

With this image we can can see the structure added by mkfs.ext4, and where on the drive the ext4 data is located.

Its worth noting this image doesn’t actually differentiate between "ext4 bytes" and "non-ext4 bytes". That is, there could be bytes owned by ext4, but if they are 0x00s they are color coded the same as any other 0x00... But even with this limitation, the image is interesting.

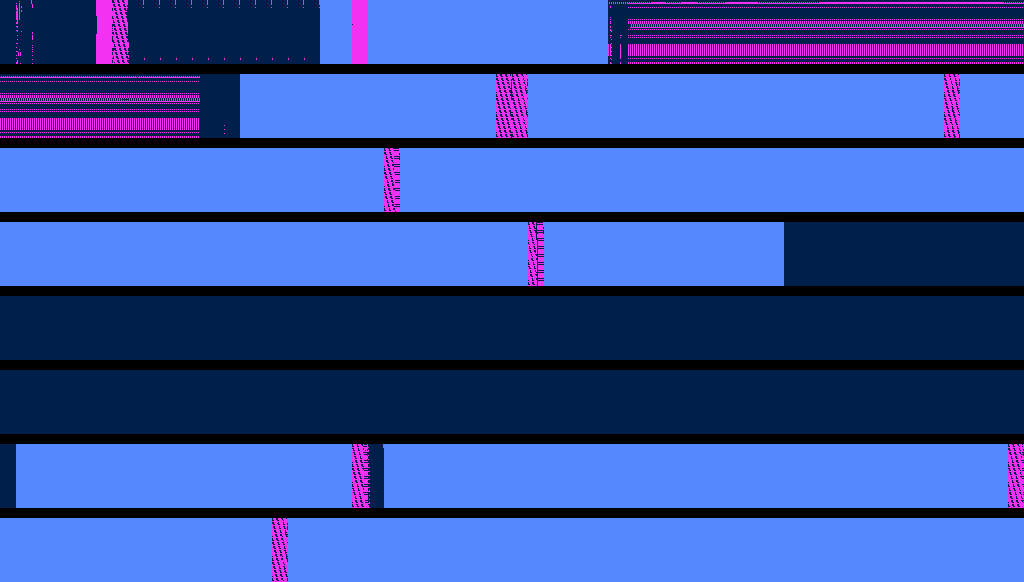

But I still wanted an image which differentiated between ext4 data and "user" data. My solution was to create a file 1024 bytes in size from /dev/urandom, and copy that file to the mounted loop device. Then, in my visualization code, when reading the blockfile, I test if "the next 1024 bytes to be read" match "the 1024 bytes of the reference file", and if they match, color code those 1024 pixels accordingly.

And with user data copied to the drive, we get this:

Which I find very satisfying... But still, I wanted an animation. So I built an animated GIF.

Between each frame, the "user data" file is copied to the drive three times... so there are three copies written each frame... This makes for a more expressive animation and a smaller GIF than if each frame was a single 'cp' of the file.

I hope you enjoy this as much as I do.

And by way of comparison, here is a similar animation, but with ext2

Here begins the ext4 rabbit hole...

Wikipedia

ext4 wiki

Admin Guide

e2fsprogs

ext4 Data Structures and Algorithms